This online exhibition presents a selection of observations and artworks created by Museum Studies graduate students in response to the COVID-19 crisis. From humorous to poignant, each piece has an emotional component — something the creators felt compelled to do or talk about. This crisis has established new ways of seeing the world.

How do these observations compare with the things that you have seen?

Student exhibit developers: Maya Colbert, Victor Feyling, Ana Navarro, Gladys Ochoa, Sara Roberts, Rose Tocchini

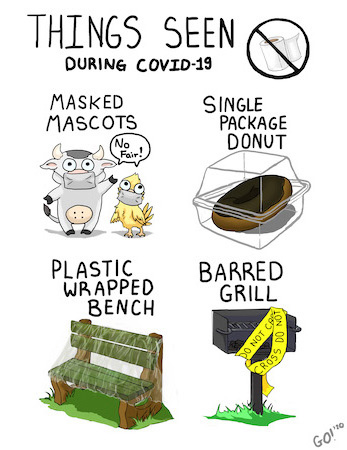

Utilizing humor to see the lighter, absurd side of the pandemic, I chose to illustrate things seen during my time watching the news and what I observed in stores, or lack of. Having existing experience working at home because of my illustration work, I am lucky to make only small adjustments to my lifestyle. There is the sense of isolation to not being able to visit friends and going out in general, however I find a comfort in being able to draw and hope to make a difference online in creating a community for others.

I am not one to practice art. I am not one to study art.

Yet, during these times of COVID-19 uneasiness and isolation, I found a small joy. That little joy is painting.

I am not original. I simply recreate what I can find on Google Images.

I am the Rona Artist.

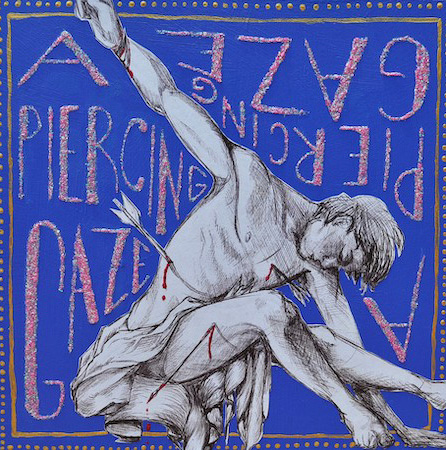

This figure is copied from a painting of Saint Sebastian by Hendrick ter Brugghen, a member of an art movement known as the Utrecht Caravaggisti for their emulation of the Italian master, Caravaggio. Saint Sebastian is known as a protector against plagues, which led to a massive spike in popularity during the Middle Ages during the bubonic plague, and again when the disease ravaged the Netherlands in the early 17th century. The arrows are thought to represent the plague, and though the wounds seem fatal, he does recover after being cared for by Saint Irene. Life is now very different than it was in 17th century Utrecht but COVID-19 likely conjures up many of the same anxieties, making Sebastian relevant again. In this particular image, the figure is drawn on the back of an old work schedule, calling to mind what has been lost as well as hope for the future.

These supplies are used to make homemade face masks. Like many, I felt the need to do something when the Coronavirus became a pandemic. As soon as the call came for homemade masks to help limit the spread, I started to sew. The masks pictured were later sent to Front Porch Care Center, a Jewish nursing home in Los Angeles. Other masks are sent to family, friends, and healthcare professionals across the country. The cat in the photograph provides much needed companionship while I shelter-in-place alone.

This image of my kitchen is an example of one of the many ways that the COVID-19 pandemic has altered daily life for myself and my roommates. It shows a collection of reusable cloth bags surrounded by a sea of paper grocery bags, often used by consumers only once before being discarded.

Known for its high concentration of environmentally conscious people (who some may call “hippies”), the San Francisco Bay Area, where we live, was an early adopter of regulations meant to limit the production and use of single-use grocery bags. Reusable bags made from cloth quickly became ubiquitous. Many carried the bags as a badge of pride, marking themselves as “eco-warriors” fighting to save the environment.

COVID-19 precautions have altered this Bay Area staple, with most stores no longer allowing customers to bring in their own bags for fear of contamination. Stores like myself and my roommates’ favorite, Trader Joes, have opted to send customers home with free paper bags. Although the bags are paper and can go into the recycling bin, we have always been in the habit of saving them for potential reuse. After a few shopping trips, we realized that the bags were piling up. What, if anything, are we ever going to use them for?

My friend found out at eight months pregnant that she would probably have to give birth alone because of COVID-19 transmission concerns. Her partner would likely not even be able to wait outside; because of social-distancing constraints and risk of infection, they had no one to watch their 2½-year-old while the baby was being born.

This is a square from a blanket I crocheted for the new baby. A single square symbolizes the anxiety and uncertainty of this time, because by itself it is useless—squares must be joined with other squares to make a blanket, just like people need to be with other people to form a community.

The square will not always be alone; it will be joined to 55 others. My friend and her baby will not always be alone; they will return home to their family. Likewise, the loneliness and isolation of this time will be resolved. Until then, the square is a symbol of the feelings of isolation, anxiety, and uncertainty, as well as the hope of reunion, surrounding this pandemic.